05 July 2022

Ever had a conversation with a friend who uses statistics to make their point? Seen business presentations with large graphs about how specific metrics have changed over a period, for good or bad? Heard politicians make speeches citing figures such as crime rates, inflation, employment rates, etc.?

Data is ‘used’ everywhere. Anywhere you look, information is being collected. That information is then oftentimes twisted and churned to get results artfully and casually showcased with the specific intent to make you draw an inference. Typically to suit the presenter’s agenda. This agenda could be anything. It could be as small as drumming up some eyeballs to get more viewership for a movie or as serious as selling a financial product to unsuspecting consumers.

While the abuse of data has been rampant for centuries, the world today as we know it, is built on Data. It has been a positive game-changer in research, technological innovation and even policymaking. Whether it is finding a planetary body in a faraway galaxy or deploying more cops to a particular locality for security, many achievements were possible simply because some people decided to take a data-driven approach rather than one based on intuition alone. And as we have stepped into the age of information (Big Data, as it’s often called), the data that we collect, analyse, and interpret is changing the world every second, and these changes are substantial.

However, we aren’t here to take a stance on data or statistics; we are here to find out why and how statistics easily fool us.

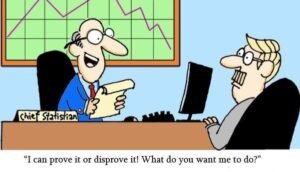

Statistics is a powerful tool to sway the masses. Random statistics in newspapers or on the internet force us to controlled conclusions rather than the truth. Even when the data mentioned by people or organizations is correct, they tend to mislead us by hiding a part of the story. These stats are more often than not, raw and can be easily manipulated to fit any narrative. Unless you know where to poke a hole or the context behind it, you will most likely become a victim of the phrase “numbers don’t lie”.

Let’s look at an example. TED beautifully explains this concept by using the commonly used toothpaste marketing line that we have all seen before – “9 out of 10 dentists recommend this toothpaste”. It may be not easy at first to realize how this line has been manipulated to sell more toothpaste. Let’s create two lines to better set up what happened during the survey and what was advertised.

Catch the difference?

Catch the difference?

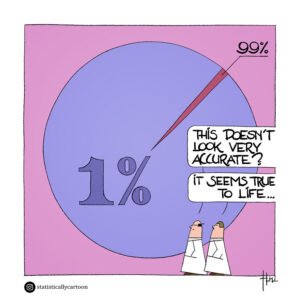

When this ad first came out in the U.K. (where the survey was conducted), there were more than 2,00,000 practicing dentists. In that scenario, the smallest possible sample size to run a viable survey would have been 400 dentists. Any study conducted with less than that number is simply wrong. This toothpaste brand only surveyed 10!

Would you or any onlooker pause in the midst of a busy day to investigate the actual number of dentists surveyed? If you do, you’d definitely raise that 10 people is too small a population size to assess the usefulness of a product and also understand that the study looked into no gender, age, or racial bias.

Let’s look at one more example of the ‘bad’ face of data. On social media, we see ‘facts’ with large numbers splashed across our screens. We tend to be swayed by the message of the author. Know that when Apple says “50% of customers”, that denominator is different from when Google says 50%. And this 50% is largely different from Dell’s and nowhere near Xolo’s 50%. Be aware that customer base, geography, market share, etc., matter greatly! We must always know how to separate brandy from cognac when it comes to statistics.

We need to understand that data by itself, is like popcorn. One or two don’t make sense and are inadequate. However, you take more than a handful, and suddenly, it is sufficient. While the popcorn remains the same for everyone, the outcome can be influenced by certain factors – Adding butter, flavoring, and a certain amount of salt can alter the outcome by boosting its desirability. In the case of data, this tweaking is done with sampling, modeling, and storytelling.

We call such faces of Data ‘The Bad’, as these decisions may have a marginal influence on our lives The toothpaste we choose to use or the laptops we buy have a relatively little impact on our lives. While it may not cause great discomfort, we have nevertheless been influenced to act based on faulty statistics.

What we know for sure right now is that trying to alter the messaging of raw data to suit the needs of the claimant is unbelievably easy. What happens when such manipulation is aimed at influencing more serious decisions of ours?

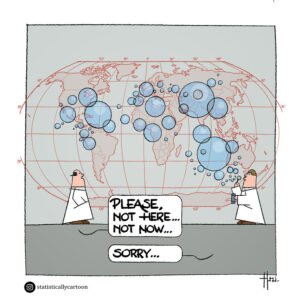

Let’s take this example. In the 2012 presidential debate between Barack Obama and Mitt Romney, the conversation turned towards which candidate has created or will create more jobs for Americans.

Barack Obama stated to the crowd, “Over the last 30 months, we’ve seen 5 million jobs in the private sector created”.

Point to Barack Obama, right?

Let’s back up a bit. The real picture emerges when we break down the numbers mentioned by the president. We are going to break it down into two parts– the dates mentioned and the overall jobs the government has claimed to have created.

While the president was not lying, the truth was distorted.

On the other end, Romney stated, “If I’m president, I will create/help create 12 million new jobs in this country with rising incomes”. While this may seem relatively more impressive than what Obama had stated, economists had already forecast that the economy would be relatively stable over the next 4-5 years and that 12 million new jobs would be created. Most importantly,

On the other end, Romney stated, “If I’m president, I will create/help create 12 million new jobs in this country with rising incomes”. While this may seem relatively more impressive than what Obama had stated, economists had already forecast that the economy would be relatively stable over the next 4-5 years and that 12 million new jobs would be created. Most importantly,

the job market was expected to take on this path irrespective of who would be at the White House.

In this case, Mitt Romney just borrowed goodwill from a stat (situation) that was bound to happen and claimed ownership of it. He wasn’t lying, but the truth was distorted here too.

In both cases, the audiences were swayed to believe the figures their presidential front runners mentioned for two reasons.

We tend to be swayed easily when an emotion is attached to the discussion. That emotion pushes us to believe or reject an argument without questioning its authenticity, irrespective of whether the conversation has been built on facts. Emotions blind us from the truth.

We call this section ‘The Ugly’ as the impact of such ‘data’ on our decisions is much larger than we think. The presidential candidate we vote for will have a socio-economic impact for the next few decades. Therefore, it is critical that we take our time, ask the right questions, and dig into the data before making up our minds. There is a massive difference between purchasing toothpaste and voting a candidate into office. President George. W. Bush pushed for and accelerated financial deregulation during his first term in office. Banks lent subprime mortgages to more and more home buyers, which finally triggered the Great Recession of 2008, the impact of which we still feel today. When Bush ended his presidency in 2009, millions of jobs were lost, large multinational companies filed for bankruptcy, and today’s economy has largely taken on a different path.

Need we talk about President Trump?

Swearing you’ll never believe in ‘numbers’ again? Hold on. Don’t throw statistics out of your window just yet.

By just learning the fundamentals of statistics and understanding how numbers operate in the real world, you can –

In business too, the common vein between a successful start-up, a profitable MSME business, and a large multi-billion-dollar conglomerate lies in the gathering, questioning, and analysis of data that flows through it, to take informed decisions. This makes data the good buddy that people lean on quite heavily if they want to become profitable.

If this is all it takes, then why aren’t more and more people learning any statistics? One word – Fear! The power of fear is tremendous in making one think and act differently. It is this fear that forced us to hate math as a kid or prevent businesses from using their data to make meaningful decisions. Those who decide to take on a more dynamic and learning-oriented mindset usually lean towards exploring data to make decisions. The rest have yet to embrace the possibilities.

Ironically, the biggest challenge of changing from a culture that makes decisions based on heuristics to one based on data is not the cost. But, ask a business why they haven’t evolved to a learning culture, and they will most likely cite the cost involved to make that leap – the cost of time and money.

What we suggest is that you take small baby steps into drawing from ‘the good’ of data. This way, we can slowly build confidence and start chipping away at that fear of the journey. As we make progress, we have seen the mindset changes.

I look at this as like losing weight. Initially, it is tough, and many factors are working against us. However, as we make slow and considerable changes to our lifestyle and start working out, the fear disappears, and quickly you are a few steps closer to achieving your goal.

And along the journey, you meet other individuals, leading to co-learning, which further accelerates you on your way ahead. Before you know it, you have learnt all the basic concepts, how and when to ask the right questions and have a better understanding of how numbers are used to manipulate people.

Only this time, you are on the side where the grass is greener.